Thirteen hours of unrelenting Mongolian steppe landscape unfolds, a rolling valley of bronze grass broken by random little villages of gers and industry. There are gaping slashes of the land, from abandoned sand quarries.

Ger hospitality

There is a parallel road running alongside the tracks, but rarely do I see any car or truck on it. The land looks barren but there are herds of sheep, cows, horses, and occasional yaks grazing.

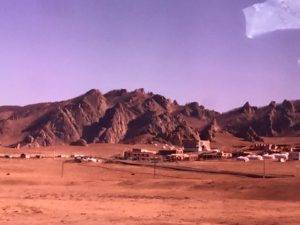

Mongolian Village

A flock of small bluish birds suddenly burst flying from a brush cover, disturbed by an unseen threat, the train perhaps? Beyond the presence of man’s habitation, encouraged by the mobility of the train track and the road, lie an ocean of brown grass as far as the eye can see, to infinity, beyond the horizon.

Nomad Shepherd

You lose direction, there is no landmark to orient your space. The train chugs along, a marvel of conquest of this vast land, even in these modern times.

Aliens on the Steppe

I imagine how this trans-Mongolian iron horse looks from space, if visible at all. And I am transported by the romance of Chingiss Khan and Kubla Khan who with mere horses and arrows ruled an empire spanning all of Asia and Europe in the 13-14th centuries, the largest contiguous land empire in the history of the world. Scholars have theorized that the Mongols’ success in conquests was due to a superior communication network, the Yam, a series of courier posts relaying a medieval pony express system. A Mongolian rider can deliver a message traveling 200 miles a day, and be relieved by another rider at these relay stations to continue the journey, non-stop. Today, every Mongolian holds this network in a smartphone in his hand.

In the shadow of Chingiss Khan

On this last leg of my journey, a young man shares my double, de luxe class compartment. He speaks excellent English and he is gallant enough to exchange my top bunk with his lower bunk. My travel agent purchased my train tickets and didn’t pay attention to bunk arrangements. This train is much newer with more room and an ensuite shower, sink and toilet that is not smelly! Michael was born in Ulan Bator, an only child of parents who worked in the US, but returned home five years ago. He lived in Las Vegas and California as a teen and went to high school there. He is 21 years old, still in college studying history, and travels often whenever he has the money, to Moscow and Beijing, where Mongolians do not require a visa. He says he has a US green card and likes to visit again but he can’t afford the travel. At our parting I give him the rest of my MNT, 15,900 Mongolian Tugrik, about $8. He seems to have a touch of Asperger’s in the way he is alienated from his peers and the way he twitches in his expression whenever he gets animated by his favorite subject, a preoccupation with the physiognomy of the different races and ethnic groups. He challenges me to tell a Slav from a Mongol, Korean from Japanese, a Turk from a Khazak, etc. I get bored quickly and I allow myself to be mesmerized by the passing view.

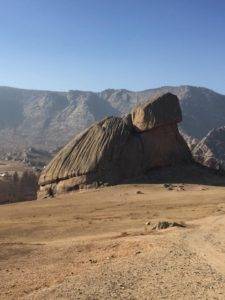

Turtle Rock

After thirteen hours we are at Dzamynude, the Mongolian border, where we stop for 105 minutes for customs check. Half an hour later we arrive at Erlian at 9pm, the Chinese border, where we pause the journey for 260 minutes for passport processing, to switch dining cars and to change the train wheel-sets, bogies, to China’s narrower gauge tracks. We are not allowed off the train. The train is taken to a shed and separated into two. Then each car is hoisted up by powerful jacks, passengers with it and all, its wheels removed and a different set reinserted. We experience sudden jolts and clunks and gnashing of iron rails and wheels, and after three hours we are chug-chugging along on our new set of wheels at 1:20 am. My young man sleeps in his top bunk through it all. There is pitch darkness outside my window. The heavens with stars twinkling do not have enough brightness to illuminate the Gobi desert and the Great Wall into view, as well, the moon is just a sliver of a crescent swoosh in the sky. I awake to the dawn at 6:30 am and gradually the varied landscape of the Chinese countryside unfolds. There are ice-peaked mountains in the horizon, green valleys in autumn colors, golden wheat, red-leaved and orange trees, flowers, vines burdened heavily with grape clusters, cascading waterfalls, winding rivers and wind-swept hills, badlands and gorges.

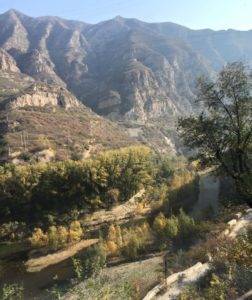

P Chinese landscape

The sun soon bursts with explosive energy and the air is warm. My young man wakes up, does his morning ablutions while I have breakfast of scrambled egg. He declines my invitation, says he will have a McDonald’s at our stop. Beijing is announced, the final destination of my trans-Siberian rail journey, from Moscow, 6540 miles.